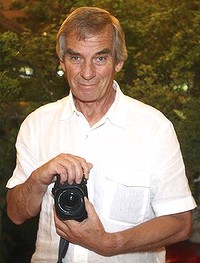

Robert Whitaker, the acclaimed photographer of his 1960s generation, was a front row witness to the tumultuous decade. As a photographer, a profession glamourised by Michelangelo Antonioni in Blow Up (1966), a degree of hedonism was compulsory. A larger-than-life macho adventurer, who was mauled by Beatles fans and wounded by the Vietcong, he was never without a camera.

Mick Jagger called him ”Super Click”. His close friend Martin Sharp called him ”A handful. He was full on.” Whitaker said he photographed the 100 most important figures of that decade.

He was also famous for documenting the Beatles at their pinnacle, but his legacy goes deeper. If the ’60s was important, then Whitaker, who imaginatively helped shape its images forever, is significant. Last Friday, Steve Jobs was given 10 minutes on the BBC. When Whitaker died, he received seven minutes.

Robert Whitaker was born on November 13, 1939, in Harpenden, Hertfordshire, the son of an Australian who flew in the RAF during World War II. He was educated in London and was encouraged from an early age to take an interest in the visual arts. He was particularly fascinated by the work of Salvador Dali.

He emigrated to Melbourne in 1961, a ”10-pound Pom”, and was soon part of a bohemian circle that included the poet Adrian Rawlins, Georges and Mirka Mora, Charles Blackman and patrons John and Sunday Reed.

Martin Sharp became a lifelong friend, as did pioneering ”filmer” Albie Thoms. Rawlins took Whitaker to see Thoms’s Revue of the Absurd in Melbourne in 1963. The Reeds were connoisseurs of young talent (Sunday had famously nurtured the painter Sidney Nolan). In 1964 the Reeds, exercising their avant-garde taste, exhibited Whitaker photographs at the fledgling Museum of Modern Art of Australia in Melbourne, co-founded by the Reeds and Georges Mora.

Simultaneously, in a cultural jolt, the Beatles visited Melbourne. Whitaker was in the crowd as the Beatles greeted fans at the Southern Cross Hotel. Savagely mocking Beatlemania, John Lennon gave the screaming mob a Nazi salute.

Rawlins introduced Whitaker to the Beatles manager, Brian Epstein, to take photos of him for the Australian Jewish News. Whitaker adorned Epstein’s portrait with superimposed peacock feathers. That clinched it for Epstein who, now enamoured of the work and the man, offered to manage Whitaker and asked him to be his house photographer and artistic adviser.

Arriving in London, Whitaker promptly photographed the pop elite, including the Beatles, Eric Clapton with Cream, and many others. With his job, wit and joie de vivre, he was a social hit. As the Beatles’ photographer he was on a unique perch to record ”Swinging London” in high gear.

The new look reinforced the Beatles’ appeal, intuitively recognised by young people worldwide. The new music was marketed with fresh visual aesthetic. With unparalleled entree to the Beatles, Whitaker was at the centre. No celebrities today would give the kind of access he had. Whitaker skilfully combined the vulgarity of a paparazzo with the care of the fine artist. Dali later gave Whitaker intimate access as well, resulting in startling portraits Whitaker described as ”shooting into every hole to get into Dali’s brain”.

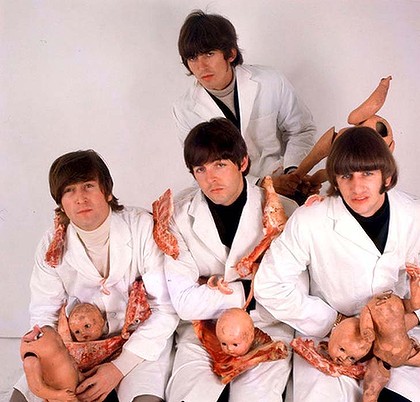

The Beatles/Whitaker collaboration climaxed with the sensational ”butcher” album cover for Yesterday and Today, featuring raw meat and cut up dolls, satirising Beatlemania and pop marketing. Whitaker, stunned by witnessing Beatlemania from the inside, was visually punning: these were normal, literally flesh-and-blood men. Capitol Records pulled the image after protests.

Coming after Lennon declared the Beatles were more popular than Jesus, dismembered dolls and meat offended many.

Whitaker stated in 1966: ”All over the world I’d watched people worshipping like idols, like gods, four Beatles. To me they were just stock standard normal people. But this emotion that fans poured on them made me wonder where Christianity was heading”. In 1994, an original album sold for $25,000.

Sharp arrived in London and he and Whitaker collaborated on explosive imagery, including art for posters, the London Oz magazine and Cream’s Disraeli Gears hallucinatory album cover. The influence of Sharp’s graphic genius and artistic spirit was powerful. Crossing between counter-culture and fine art, they created classic images of the London psychedelic period. Friends like Thoms, Richard Neville, Germaine Greer, Felix Dennis, Louise Ferrier, Birgitta Bjerke, Clytie Jessop, Angus Forbes, Jenny Kee and many other talents had their own solar system in London. Bob Seidemann, creator of the legendary Blind Faith cover, photographer of Janis Joplin and the Grateful Dead, described Whitaker as ”generous, gentle and thoughtful – always lending me cameras”.

Last week, friend Mirka Mora, 83, recalled that ”Bob had tight jeans and a nice bottom. Bob inspired everybody, it was an event when he was around because he was always photographing, which made people do things, like magic.”

In 1968, Whitaker collaborated with Sharp on the film, Darling, Do You Love Me? starring Greer. The comedy short, given the green light by Bruce Beresford and his colleagues at the British Film Institute, mocks personal commitment as Greer terrorises a Woody Allen-Sharp hybrid. Expressionist imagery, a dramatic semi-nude Greer and Kabuki make-up recall the silent films of Man Ray, Luis Bunuel and Dali.

Whitaker was creatively unpredictable; working in battle zones, using an underwater camera on land or taking close ups of Dali’s nose hairs. He once half-joked that photographing up Dali’s nostrils was scarier than his Vietnam work. Defying a love generation image, he became a war photographer, covering conflicts in Cambodia, Pakistan and Israel. He had an adventurous, patriotic streak, once completing dangerous work on a secret mission for the British government.

The 1970s found him on an Oxfordshire farm with his wife, Sue, raising a family of three, drawn back into photography by exhibitions and books. Sue, a beautiful woman and good sport, posed nude with Dali for some classic photos in a Pirelli calendar by Whitaker. Dali had advised him to always travel first class, and spotting a Pirelli billboard, said to Whitaker ”Come on, let’s make some money!”

As countless photographs reveal, Whitaker made much more than that.

Robert Whitaker is survived by Sue, and by their daughter and two sons.

Philippe Mora